I Felt the Explosion 12 Miles Away

Reflecting on the 30th Anniversary of the Oklahoma City Bombing

Did you know you can feel the force of an exploding truck bomb 12 miles away? I learned a lot of things on April 19, 1995, the day of the Oklahoma City bombing. That was just one of them.

I was born, raised, and currently reside in Yukon, Oklahoma, a suburb just west of Oklahoma City. A couple of years ago, the Census Bureau did a study that revealed 60% of young adults live within 10 miles of where they grew up. While that’s true in my case, just know I have visited all 50 states and half a dozen countries. I’m not one of those guys who never left his hometown. I left Oklahoma, saw the world, and came back home. I choose to live here.

I’ve asked people all over the country what they think of when I mention Oklahoma. Most of them know our state song, “Oklahoma,” from the famous musical. Cowboys, cattle, and oil are always high on the list, along with Native Americans, country music (Garth Brooks and Toby Keith come up a lot) and of course, tornados. Everybody in Oklahoma has a good tornado story.

And then without fail they’ll say, “oh, isn’t that where that bombing happened?”

Just like tornados, everybody here has an Oklahoma City bombing story, too.

Here’s mine.

I graduated from high school in 1991. Over the next four years I attended two different colleges, earned zero degrees, worked at three different Pizza Inns, three different Pizza Huts, Heavenly Pizza, and Long John Silver’s. I even spent a summer working at my future mother-in-law’s BBQ restaurant where “other duties as assigned” included wearing a rented pig costume and waving a “Kiss the Pig” sign at passing motorists.

Things changed in 1994 when I got a job at Best Buy. I started in the computer department and moved to the “tech booth” — this was before “Geek Squad” existed and probably before anyone current Geek Squad employees was born. I grew up during the home computer revolution so installing video cards and running virus checks was nothing new to me, but it also got “computer technician” on my resume and in April of 1995 I was offered a job as a helpdesk technician in a federal building.

No, not that one. Thank God. But we’ll get to that.

I mostly worked the evening shift at Best Buy and so on the morning of April 19, 1995, I was lying on the living room couch flipping TV channels when I heard the garbage truck driving slowly past my house. Actually, I didn’t hear it as much as I felt it, that low rumble that rattles your windows and tickles your guts.

Convinced I had forgotten to take the trash out, I leapt from the couch and ran to the front door only to discover… no garbage truck in sight. And then it hit me… Tuesday’s not even our garbage day!

Huh, I thought. That was weird.

By the time I got back to the couch, the channel I had landed on — KFOR, News Channel 4 — had already interrupted local programming with a special bulletin.

“Something has happened downtown,” a reporter said. “We don’t know what.”

I went back outside and looked east. By then I could already see black smoke climbing into the innocent Oklahoma sky.

One time when I was a kid, I went to visit my uncle who lived out in the country and watched him burn a pile of trash. That’s when I learned the difference between white smoke, like the kind that comes from factories, and black smoke. The smoke I saw on April 19 was the blackest, most evil-looking smoke I have ever seen.

The next thing I did was call my wife, who was working in an office about halfway between me and downtown. I relayed to her what they were saying on the news (“There’s been an explosion of some kind…”) and she said, “We thought a truck hit our building.”

For the record, my wife’s building was 5-6 miles west of where the Alfred P. Murrah building was located. That’s when it dawned on me that the rumbles and rattles I had heard earlier that morning wasn’t the garbage truck. It was the shockwave from the blast, hitting our house.

We lived twelve miles away from downtown.

On television, the next several hours were pure chaos. For all practical purposes there were no cellphones in 1995, and the internet was still in its infancy. The best way to get news updates at that time was through television and radio. And in times of crisis, things got messy.

Every local journalist who had access to a microphone drove as fast as they could to downtown Oklahoma City. Anyone who was already there was grabbed by the arm and yanked in front of a live television camera. What did you see? What did you hear? Everything anyone said was immediately broadcast live to millions of viewers. Even if it was wrong.

One of the first things somebody said was that they had seen two Middle Eastern men racing away from the site of the explosion in a truck. Within minutes, every journalist on every station repeated it. I hate to say it, but in Oklahoma — and especially in the 1990s, hot off the Gulf War and Desert Storm — there were already plenty of good ol’ boys being “not very nice” to Middle Eastern men here in the Midwest. Now, on live television, reporters were blaming them for the attack. There were multiple reports of random Middle Eastern men being randomly attacked. There was a legitimate concern that someone in a jacked-up pickup truck might find the perpetrators before law enforcement had a chance.

Another false rumor that spread was that law enforcement had discovered a second bomb. Not to be outdone, KFOR reported the FBI had confirmed they had found a third bomb, even bigger than the first two. (None of that was true.) It was terrifying to watch emergency personnel and even random citizens running toward the building to help and immediately running away from it in sheer panic.

In the middle of a chaotic event, people aren’t able to put all the pieces of a puzzle together. Inside the Murrah building was an FBI office. Those offices often have non-operable weapons for training exercises. The reason I know that is because a coworker of mine, a sweet, innocent-looking Hispanic woman, was once asked to carry a real but non-operational hand grenade through airport security as a test. I always felt and even seem to recall them saying that’s most likely what someone found in the street that day, something from that FBI office, but the details have been lost. Then again, when a six story building explodes, there’s no telling what people found laying out in the street that day. Anything that was metal with wires sticking out of it would have understandably made anyone jumpy at tje time.

Now all these reporters were reporting from the ground, as were their cameramen. Once they got close enough, the view of the Murrah building they kept showing looked like this:

The problem with this angle was that it was 2D. It looks as if you had a square cake and you sliced the end of it off, revealing the middle. This view did not show the extent of the damage. It wasn’t until the local news stations got their helicopters into the air that you could see the real scope of what had happened.

It wasn’t like slicing the end off a cake. It was like rolling a bowling ball into one. The curvature in the roof of that view still gives me chills. All of it does, really.

Also, that big hole in the ground? That’s right below where the daycare was.

My cousin worked in the daycare.

I want to tell you a random story about Oklahoma. A couple of years ago, my dad tried to do a U-turn in the middle of a two-lane road and in the process he accidentally backed up a little too far and got stuck in a ditch. He was on his way to my house, so I hopped in my car to go see what I could do. By the time I got there, a random stranger had already stopped and was trying to help. The guy and his family were leaving for vacation but “had a few minutes before they had to be at the airport” and also had a tow rope. He tried pulling my dad’s truck out, but unfortunately the rope snapped and since I had arrived, they left. Two minutes later, another fellow stopped, an old Hispanic man who spoke little English and arrived in a truck with tow chains. After a bit of tugging and pulling, we got my dad unstuck. As the man was preparing to leave I tried to give him a $20 and he said “no no no!” before speeding away.

That’s an Oklahoma story. Everybody here has a story about helping someone, or somebody helping them. I bring my neighbor’s trash cans up from the street if I wake up before he does. He’s mowed my lawn before, for no particular reason. People here smile and wave when they pass one another and help each other and hold doors for each other and pay for random strangers’ breakfast on occasion. That’s what Oklahoma is.

And when that reporter told me that two Middle Eastern men had just blown up a building in my town, I believed her. I believed her because I just knew that anyone capable of committing such a horrendously despicable act of violence could not be from here. Whoever was responsible for this act, I was sure, would not look like me. They would be from somewhere else, some place far away.

We were wrong, of course.

The funny thing is, people here don’t talk about Timothy McVeigh much. Instead, they talk about the victims and their families. Most people know somebody who was affected by the bombing.

Few people remember the name Richard Reid, but most remember his nickname. Reid was the Shoe Bomber, the guy who packed explosives into his tennis shoes and tried to blow up an American Airlines airplane back in 2001. He did not succeed in blowing up the airplane or anything else, and more importantly, he did not succeed in destroying America. The only thing he succeeded in doing is forcing millions of travelers to take their shoes off every time they fly.

Timothy McVeigh killed 168 people on April 19, 1995, including 19 children and my cousin who were in the daycare. But he didn’t make a dent in America. Most people don’t know or remember what his motive was.

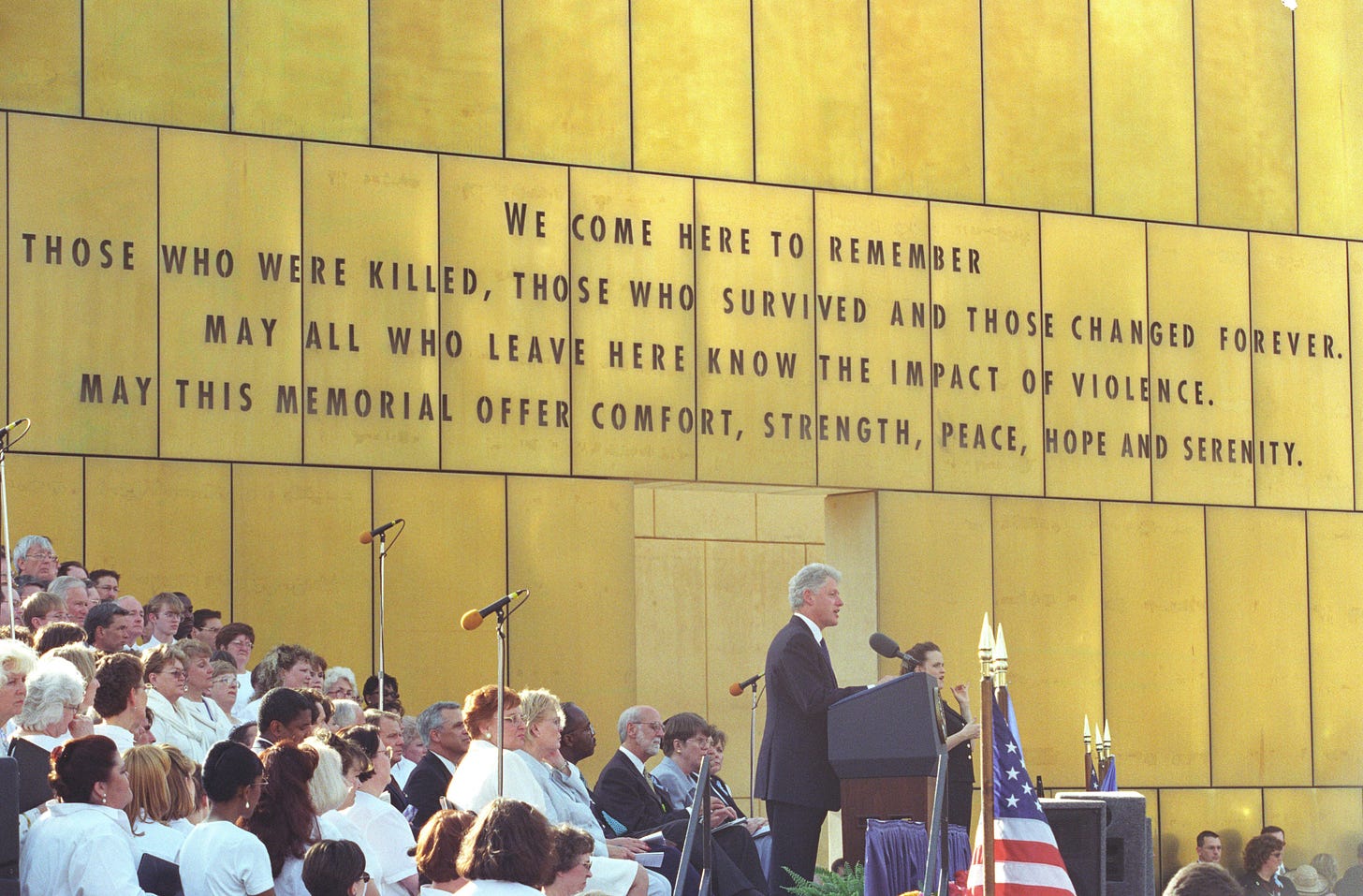

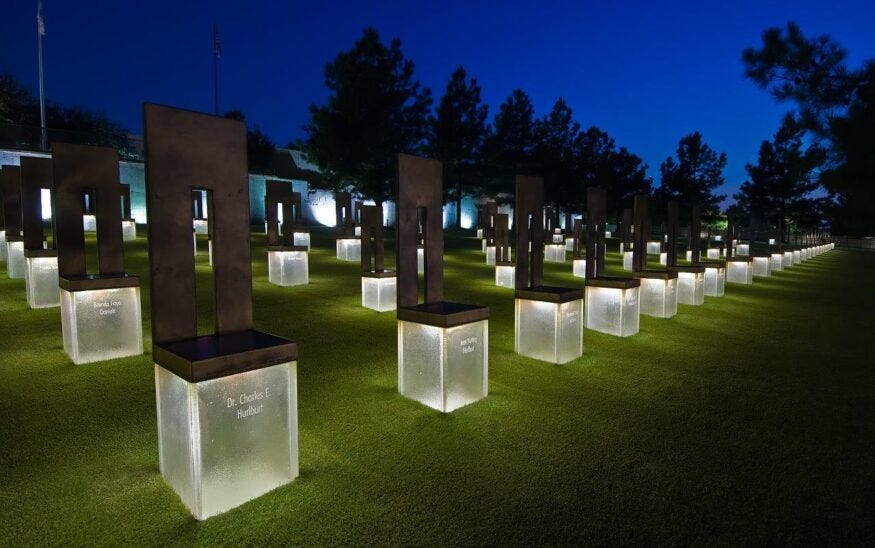

Instead, here in Oklahoma City, we have the Bombing Memorial, which was built where the Alfred P. Murrah building once stood.

The two walls on either end of the Reflecting Pool permanently display the times 9:02 and 9:03 — before and after the bombing. Off to the side are 168 chairs including 19 smaller ones honoring the deceased children. If that doesn’t choke you up, there’s a chain link fence on the west wide of the memorial where visitors leave stuffed animals and other baby toys. I’ve been to the memorial many times and it’s never a happy time, but it always feels important.

This weekend is the Oklahoma City Memorial Marathon. Last year about 25,000 people ran in the marathon and this year, being the 30th anniversary of the bombing, who knows how many people will show up. Thousands more stand around the city, handing out bottles of water and snacks. My friend Molly is organizing a Mrs. Roper Costume and Dance Off this year in a park when the runners will pass through. My kid did the 5k a few years ago. It brings the whole city together to celebrate and remember.

One week after the bombing, I started that new job working on a helpdesk in a federal building. When I started, the building was completely open to the public. Anyone off the street could saunter on in and walk around. Things changed. Now there’s a fence around the perimeter, and guards with guns who check the sticker on your vehicle and your badge. Sometimes there are random vehicle checks and sometimes for reasons not known to me (and just as well), there have been more secure measures. So, that’s what Timothy McVeigh achieved. He didn’t change the world. He just made it a little more difficult for me to get to work.

Sometimes I think about all the people who were there that day who had nothing to do with the government, who weren’t the target of McVeigh’s ire. You tend to think about these things when you find yourself working in a federal building a week after someone just blew another one up a few miles away.

Many years ago — 20, maybe — there was this new guy at work, Jason. The guy seemed nice enough and knew enough about networks to hit the ground running. There were only about half a dozen of us working together in a pretty small room, the kind of place where everybody could smell what everybody else had brought for lunch. A couple of times, Jason got off the phone and slammed his handset down so hard I thought he might have broken it. He might have broken his desk. One time he got up and punched the wall harder than Rocky could have. The dude had some serious anger issues and management stepped in pretty quickly.

One afternoon, before he left, Jason told me he had been working in the Murrah building on the day of the bombing. He said he didn’t remember the explosion, only the sensation of falling. He ended up sandwiched somewhere in darkness between tons of concrete. His arm was bleeding so badly that he wrapped a network cable around it to serve as a tourniquet and stop the bleeding. He said it was night when they finally found him and pulled him out and the bombing took place at 9:02 AM so, he was there for a while.

I’ve had nightmares about his story.

I want to share with you one last memory. The day after the bombing, Oprah arrived to interview, among other people, the last survivor pulled from the building. Then, Dan Rather arrived. And Connie Chung. And Bryant Gumbel. And Tom Brokaw. And dozens of others. The worst was Geraldo Rivera, who spread every rumor and conspiracy theory anyone told him in an attempt to boost his ratings.

Much of the journalism was sensationalistic. One of our local news channels reported that the Nation of Islam had called the station and claimed responsibility for the bombing, a claim they repeated on the air. Both the national and local journalists were so desperate to be the first to report breaking news that ultimately they reported everything, a lot of which turned out to be untrue. Even worse were the reporters who would run up to exhausted and emotionally drained emergency workers and shove microphones and cameras in their faces. Tears equal ratings!

But that’s not my memory. My memory is that a few days after the bombing, maybe a week or so, all those reporters packed up their cameras and news vans and left. The national news moved on. And I remember thinking… we’re still here. There’s a giant pile of concrete and glass and blood in the middle of my city. Our story was not over, but like a turnip once all the juice had been squeezed out of the story, the world moved on.

I think about that every time the news covers a national disaster, like the wildfires in California or the floods in North Carolina or a school shooting. The media swoops in, gets their story for a few days, and then it’s off to the next one.

This Saturday, if you turn on the national news they’ll probably mention the 30th anniversary of the bombing. Maybe they’ll mention the marathon. President Bill Clinton is planning to visit this weekend. He came to Oklahoma back in 2000, when the memorial was first built.

And then, they’ll all go home.

And 168 empty chairs will remain here in Oklahoma.

Including my cousin’s.

A very powerful piece, Rob (should I call you Flack?), brought a tear or three to my eyes. My great-grandmother was born in Oklahoma Territory, moved to Canada as a bride. She had that same sense of kindness and giving you describe.

Excellent article!